In 2017 I wrote Why Do Our Bodies Attack Us? Like many of us, I wondered WHY did I have a chronic condition (otherwise often known as an underlying condition). Most of my working life has been about root cause analysis – naturally I apply that to myself! It is a bad move, I don’t recommend it, you can drive yourself nuts!

More recently, December 2021, I wrote Will Society Adapt? When? How? looking at society’s lack of acceptance of chronically ill people. I specifically noted I wasn’t looking at environmental impacts in that article, but we can’t ignore the impacts we ourselves, as a species, have created in the same span of the last 100 years or so. In that article I proposed society has yet to adapt to this new chronic state of health, and I referred to my generation as being the first generation of chronic people in any great number. I essentially attributed our survival to improvements in medical science keeping us alive, but why do we fall sick in the first place, in ever increasing numbers?

Regular readers will know I am a big supporter of the work of Julian Cribb, an Australian author and fantastic science communicator. He has recently released Earth Detox – How and Why We Must Clean Up Our Planet.

Every person on our home planet is affected by a worldwide deluge of man-made chemicals and pollutants – most of which have never been tested for safety. Our chemical emissions are six times larger than our total greenhouse gas emissions. They are in our food, our water, the air we breathe, our homes and workplaces, the things we use each day. This universal poisoning affects our minds, our bodies, our genes, our grandkids, and all life on Earth.

https://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/earth-and-environmental-science/environmental-science/earth-detox-how-and-why-we-must-clean-our-planet?format=PB

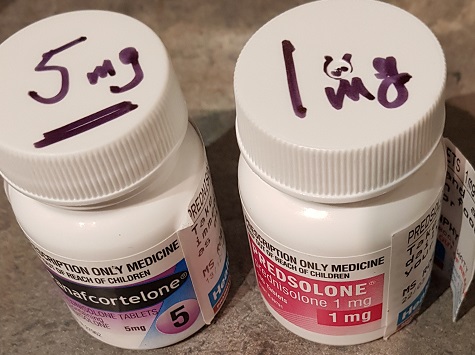

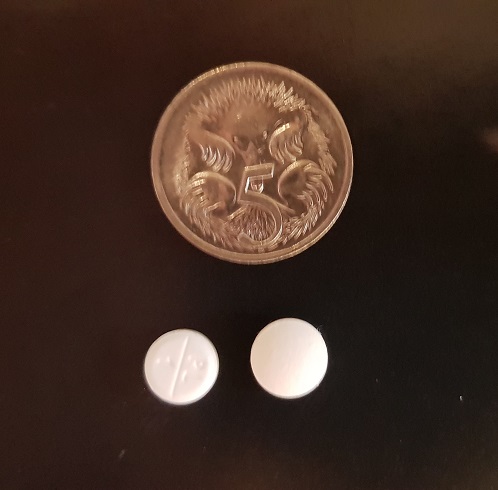

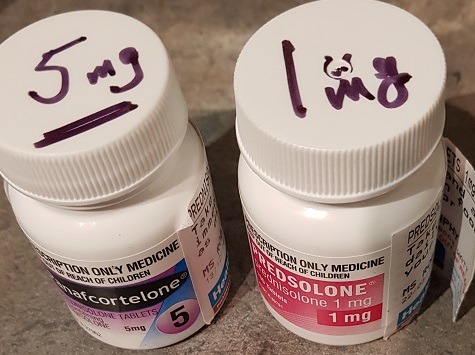

I did refer to chemicals in my 2017 article cited above. I’ve also looked at plastics in Packaging Our Pills in Plastic which includes some videos – visit that article if you are interested.

So while some science is keeping us alive, our tendency as a species to misuse other science for selfish reasons is potentially, at the same time, making us sick. Why did I choose selfish in that sentence? Let’s take plastic as a classic example. When I was a child plastic was not really a thing. Shopping bags weren’t plastic. You didn’t put your fruit and vegetables in plastic at the shops. Glad Wrap? I do remember plastic bags for freezing meat. Pills were still in glass bottles.

But plastic was convenient and we started using it for EVERYTHING! Our wild life has been paying the price for years, but it seems we have too. We just didn’t want to acknowledge that fact because that would be inconvenient and if there is one thing the human species hates, it is being inconvenienced.

Of course, all of this ties in with our population growth: if there were less of us, we’d use less of all the “stuff”. Less MIGHT be manageable. That is a big “might”.

I’m going to turn 67 this year. In my first ten years of life I lived on a farm in the middle of nowhere, BUT I was still exposed to many chemicals. Sheep dip. Top dressing. Weed killers. All before the many safety tests and regulations of today were in place.

Later I moved to the city: car fumes, plastics.

“It would be naïve to believe there is plastic everywhere but just not in us,” said Rolf Halden at Arizona State University. “We are now providing a research platform that will allow us and others to look for what is invisible – these particles too small for the naked eye to see. The risk [to health] really resides in the small particles.”

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/aug/17/microplastic-particles-discovered-in-human-organs

Yes, I have psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and a wonky thyroid (plus a few other things) and yes, there is a genetic component to PsA. What triggered the expression of the condition? After all, genes or no genes, my disease hasn’t been active all my life. What triggers any number of the conditions now prevalent in the chronic illness community, even if there are genes playing a role (in many cases, not yet proven)?

We have to stop blaming our chronic illness patients for being chronically ill, when it is very likely it is the path humans have chosen that has created many of us in the first place.

In our current situation in 2022, chronic illness has suddenly risen to the surface as a “reason” people die of Covid-19, so more people are aware of our existence. I myself am in four Covid-19 risk categories, the most dangerous to me being that I have an underlying inflammatory condition (PsA). We know Covid-19 can cause lots of inflammation: I’ve already got that going on, so I have this image in my mind of Covid-19 entering my body, running into PsA and my PsA saying, “Mate! Great to see ya! Let’s party!”

According to Professor Jeremy Nicholson, there are only about 10% of people in Western society that are “really, genuinely healthy”. You can find that quotation at 31:40 in the second video on Better Health, Together: Living with COVID in 2022.

I’m not suggesting 90% of us are at high risk of imminent death from either our conditions alone or our conditions plus Covid-19. We DO need to know which underlying conditions place us at higher risk of severe Covid-19 in order to be able to adequately take whatever additional protections may be necessary. The fact we are at a higher risk cannot be ignored. I see many on social media particularly suggesting the underlying conditions are irrelevant. They are relevant. We can’t ignore reality because we find it unpalatable. I most certainly think the politicians could separate the sad news of deaths from the statistics relating to underlying conditions. This is where the 90% really comes in – as in, it is potentially most of us!

As I am known to do, I have digressed – or have I? Covid-19 is perhaps a wakeup call. As a species we have created a state of ill-health as “normal”. Because we want our pollution and our chemicals and our plastics – but as Julian writes, we are paying the price. We’ve been somewhat quietly paying the price for a while, now Covid-19 has highlighted our vulnerability.

I know I have a chronic illness – many people do not yet know they have one. Conditions can take a while to be evident enough for the person to seek medical help. I am quite sure my PsA was active at least two years before I was diagnosed. In other situations, many people struggle to get a diagnosis of various conditions for years.

I am NOT suggesting that had Covid-19 come along in 1819, or 1719 that we would have been in a overall healthier state as a species. There were other considerations back then. However, we have changed our world, our environment, our living conditions, massively in the last 100 years. We’ve solved old problems, but created new problems.

I am a massive fan of science generally and medical science in particular, however I am also very aware of the human tendency to misuse anything we can if we see a personal advantage in doing so. Covid-19 gave us a shock: we were the Gods brought to our knees by the invisible.

We are not just destroying the environment of the planet we inhabit. We are not just destroying other species. We are possibly also destroying ourselves.