Neither are YOU lazy. The title above is stolen, with permission, from a social media contact’s tweet.

We’re not lazy, nor are we responsible for other people’s expectations of what THEY think we should or shouldn’t be able to do. Sidenote: often those expectations are based on our appearance. Refer to You Look So Healthy! for more on that.

There are four other articles you may like to browse as background material to this article:

One of the challenges we face is helping people understand the whole energy availability thing many of us struggle with. In the conversation related to the above tweet, J told me she had mowed the lawns, done the edging, walked the dog and cooked dinner. J has the same disease I do, psoriatic arthritis (PsA). While I don’t know or understand the specific expressions of many other chronic conditions, this is one I do understand. J couldn’t see me, but if she could have, my eyes nearly popped out of their sockets.

Other conditions can be very similar, but I will stick with the disease I know for illustrative purposes today.

On a great note, for PsA management, J had certainly been moving. Movement is Medicine! However, J had probably used up more spoons or internal battery than she had available. All that in one day would cost her later, as she well knows from experience.

Society conditions us, well before we get sick, as we are growing up: doing our share, work ethic, earn our way. We then place expectations on ourselves. We don’t want to be sick, we don’t want to let others down by not doing our bit. In the first few years, of course, in the back of our minds we think it is temporary. To understand a bit more on that, you may like to read Will Society Adapt? When? How? Even we ourselves have to adapt to our new normal.

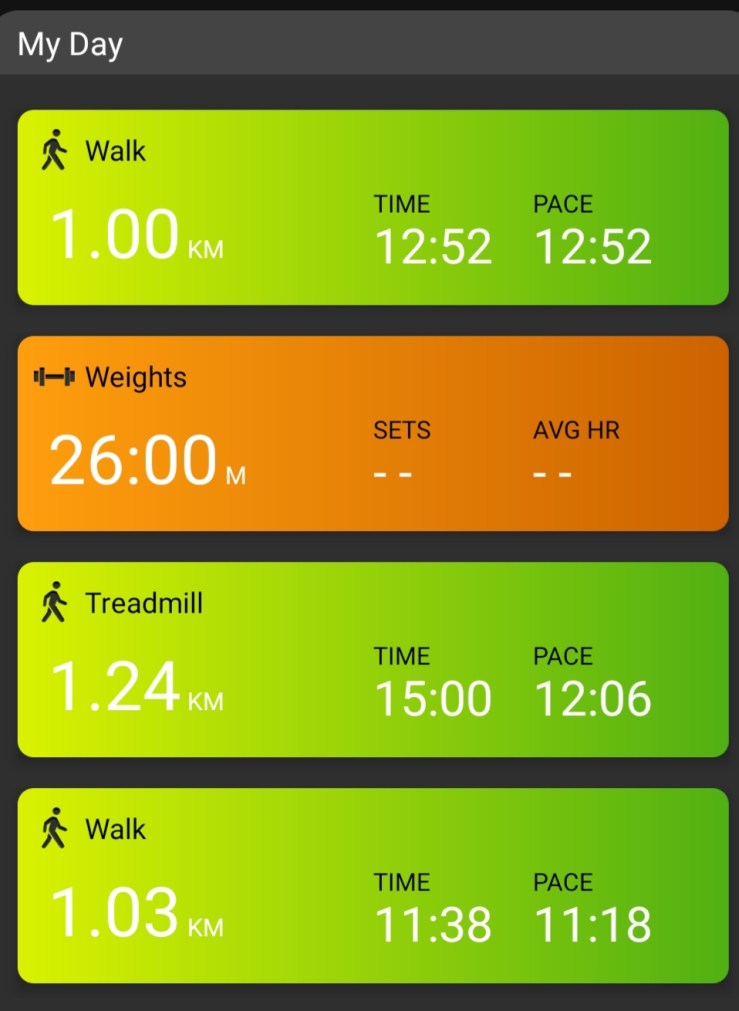

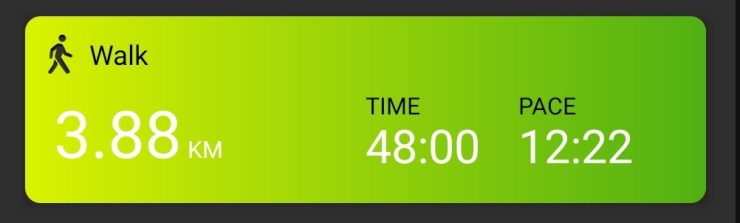

PsA is a very odd disease. At its worst for me, I can wake up in the morning with painful feet, ankles, knees, wrists, fingers; maybe even throw shoulders and neck in on a particularly bad day. I may have to use crutches to get around first thing in the morning. I’ll be unable to turn a tap on. Can’t lift the electric jug, struggle to open the coffee jar. Put on a bra? Are you kidding? Pull on tracksuit pants? Yeah, right. That sort of thing. About 11:30 am I’ll be fine. Virtually pain free. My body will have de-solidified. I’ll head out for a walk, go to the gym and do a weight training session. Sadly 160 kg leg presses aren’t happening any more, but maybe again one day…….. I am a completely different physical specimen at 4 pm than I am at 7 am. I saw my Plan B GP on Tuesday (Plan A was away), who hadn’t seen me for probably a year. She said “You look great!” This was 6:30 pm. I said to her, “You didn’t see me at 7 am!”

This can be VERY difficult for our friends, colleagues and family to understand. You need rest but you also need to go to the gym? That doesn’t make sense! Actually it does make sense and the reasons why are discussed in more detail in the above linked articles, so I won’t repeat myself.

We know, we can see it in their eyes. The doubt. The lack of comprehension of the situation.

We know people think we are just being lazy (at best) or hypochondriacs (at worst). J is right, it is VERY exhausting to be constantly explaining it to people, yet we know if we don’t explain it, if we don’t share the knowledge, social understanding and acceptance will never happen. We use analogies: spoons, internal batteries, even daisy petals. Over time our nearest and dearest do start to understand. If they want to.

If we live by the rules of pacing our activities and energy consumption, many of us can achieve a fantastic very nice quality of life, given our disease. The problem is, to OTHER people our rules can make us look lazy in their eyes – or at least that is how we can feel.

I work six hours a day. I have just entered my eighth year of having PsA, so I’ve had time and practice to build my personal pacing skills. Even so, I still feel guilty some days that I’m not “doing my fair share” at work. I have to lecture myself along the lines of this is what I MUST do or I won’t be able to work at all. I did try full-time for a while in 2019/2020 – it was WAY too much. Recently, we had a systems issue at work. That day I worked ten hours – I was petrified I was going to crash before we solved the problem. Thankfully, I didn’t, but those feelings and fears are what we live with every day. We don’t need to feel others are judging us because we MUST do less than they do in order to regain and retain quality of life and independence.

No, we do not have to vacuum the whole house in one day. A room a day would do!

No, we do not have to mow the whole lawn in one day. J, are you listening?

Spreading out those sort of tasks DOES NOT mean we are lazy. It means we are protecting our bodies, our internal battery and our quality of life.

Today I was going to go grocery shopping. But today is also weight training day. The grocery shopping can wait until tomorrow. Both on the same day would mean I wouldn’t be able to do what I have planned for tomorrow. Grocery shopping will fit with my plans for tomorrow as the overall intensity tomorrow is less.

We are not lazy. I am not lazy. Don’t let yourself be guilted into doing things that break your pacing rules, whatever they may be for you. The goal is to balance activity and energy so you achieve consistency in your state of health.